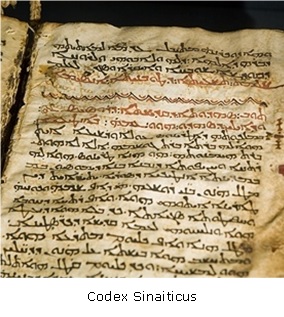

The Codex Sinaiticus or Sinai Bible, is one of the four great uncial codices, ancient, handwritten copies of a Christian Bible in Greek. The codex is a historical treasure.

The codex is an Alexandrian text-type manuscript written in uncial letters on parchment and dated paleographically to the mid-4th century.

Scholarship considers the Codex Sinaiticus to be one of the most important Greek texts of the New Testament, along with the Codex Vaticanus. Until Constantin von Tischendorf's discovery of the Sinaiticus text in 1844, the Codex Vaticanus was unrivaled.

The Codex Sinaiticus came to the attention of scholars in the 19th century at Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula, with further material discovered in the 20th and 21st centuries. Although parts of the codex are scattered across four libraries around the world, most of the manuscript is held today in the British Library in London, where it is on public display. Since its discovery, study of the Codex Sinaiticus has proven to be useful to scholars for critical studies of biblical text.

While large portions of the Old Testament are missing, it is assumed that the codex originally contained the whole of both Testaments. About half of the Greek Old Testament or Septuagint survived, along with a complete New Testament, the entire Deuterocanonical books, the Epistle of Barnabas and portions of The Shepherd of Hermas.

The codex consists of parchment, originally in double sheets, which may have measured about 40 by 70 cm. The whole codex consists, with a few exceptions, of quires of eight leaves, a format popular throughout the Middle Ages.

Each line of the text has some twelve to fourteen Greek uncial letters, arranged in four columns (48 lines per column) with carefully chosen line breaks and slightly ragged right edges.

More information: Codex Sinaiticus

When opened, the eight columns thus presented to the reader have much the same appearance as the succession of columns in a papyrus roll. The poetical books of the Old Testament are written stichometrically, in only two columns per page. The codex has almost 4,000,000 uncial letters.

Throughout the New Testament of Sinaiticus the words are written continuously in the style that comes to be called biblical uncial or biblical majuscule. The parchment was prepared for writing lines, ruled with a sharp point. The letters are written on these lines, without accents or breathings. A variety of types of punctuation are used: high and middle points and colon, diaeresis on initial iota and upsilon, nomina sacra, paragraphos: initial letter into margin.

The

work was written in scriptio continua with neither breathings nor

polytonic accents. Occasional points and a few ligatures are used,

though nomina sacra with overlines are employed throughout. Some words

usually abbreviated in other manuscripts, such as πατηρ and δαυειδ, are

in this codex written in both full and abbreviated forms. The following

nomina sacra are written in abbreviated forms: ΘΣ ΚΣ ΙΣ ΧΣ ΠΝΑ ΠΝΙΚΟΣ ΥΣ

ΑΝΟΣ ΟΥΟΣ ΔΑΔ ΙΛΗΜ ΙΣΡΛ ΜΗΡ ΠΗΡ ΣΩΡ.

Each

rectangular page has the proportions 1.1 to 1, while the block of text

has the reciprocal proportions, 0.91 (the same proportions, rotated

90°). If the gutters between the columns were removed, the text block

would mirror the page's proportions. Typographer Robert Bringhurst

referred to the codex as a subtle piece of craftsmanship.

The folios are made of vellum parchment primarily from calf skins, secondarily from sheep skins. Most of the quires or signatures contain four sheets, save two containing five. It is estimated that the hides of about 360 animals were employed for making the folios of this codex. As for the cost of the material, time of scribes and binding, it equals the lifetime wages of one individual at the time.

The portion of the codex held by the British Library consists of 346½ folios, 694 pages (38.1 cm x 34.5 cm), constituting over half of the original work. Of these folios, 199 belong to the Old Testament, including the apocrypha (deuterocanonical), and 147½ belong to the New Testament, along with two other books, the Epistle of Barnabas and part of The Shepherd of Hermas. The apocryphal books present in the surviving part of the Septuagint are 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, 1 and 4 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Sirach.

The books of the New Testament are arranged in this order: the four Gospels, the epistles of Paul (Hebrews follows 2 Thess.), the Acts of the Apostles, the General Epistles, and the Book of Revelation. The fact that some parts of the codex are preserved in good condition while others are in very poor condition suggests they were separated and stored in several places.

Little is known of the manuscript's early history. The codex has been dated paleographically to the mid-4th century. It could not have been written before 325 because it contains the Eusebian Canons, which is a terminus post quem. The terminus ante quem is less certain, but, according to Milne and Skeat, is not likely to be much later than about 360.

More information: The British Library

The Codex may have been seen in 1761 by the Italian traveller, Vitaliano Donati, when he visited the Saint Catherine's Monastery at Sinai in Egypt.

In the early 20th century Vladimir Beneshevich (1874-1938) discovered parts of three more leaves of the codex in the bindings of other manuscripts in the library of Mount Sinai. Beneshevich went on three occasions to the monastery (1907, 1908, 1911) but does not tell when or from which book these were recovered. These leaves were also acquired for St. Petersburg, where they remain.

The codex is now split into four unequal portions: 347 leaves in the British Library in London (199 of the Old Testament, 148 of the New Testament), 12 leaves and 14 fragments in the Saint Catherine's Monastery, 43 leaves in the Leipzig University Library, and fragments of 3 leaves in the Russian National Library in Saint Petersburg.

Saint Catherine's Monastery still maintains the importance of a letter, handwritten in 1844 with an original signature of Tischendorf confirming that he borrowed those leaves.

More information: Tanach Online

The Bible was written by fallible human beings.

Richard Dawkins

No comments:

Post a Comment